At 19, Donald McLeod joined the Scots Guards and was sent on his first posting to Northern Ireland in 1980 where he settled into military life. After postings to Chelsea Barracks and then on to Kenya, Donald found out that he and his fellow Guards were going to the Falklands.

“When we got there, we were thrown in at the deep end. We had planes coming from nowhere and bombing us and we came under artillery fire. We attacked Mount Tumbledown. It was nine hours of hand-to-hand fighting up a mountain. Then, at half-nine that morning, the Argentinians surrendered.”

Soon after Donald returned to London, he knew something wasn’t right: “I didn’t get hurt in the Falklands. Not physically, anyway, but I was diagnosed with Post-War Depression as it was then; now they call it ‘PTSD’.”

Following discharge, Donald came home to Edinburgh. He was holding down a decent job and living in a private flat. Suddenly things took a turn for the worse when his landlord decided to sell up, leaving Donald out on the street. His local council wasn’t able to offer accommodation assistance and he ended up sleeping - friends’ couches, park benches, parks, even graveyards - wherever he could.

“I couldn’t afford the deposit for the rents for new places. I lost all my possessions and my pictures. I couldn’t go to my family; they were scared to talk to me. It was the lowest time of my life. I thought to myself: ‘You’ve served your country, you come home and no-one seems to give a damn about you.’” - Donald

After six months, a chance meeting with a manager of the Scottish Veterans Residences (SVR) at Whitefoord House would put Donald’s life back on track. He would live and work there for the next 14 years.

The decade and a half spent there gave Donald experiences that he is keen to share with fellow veterans, not to mention the powers-that-be: “When you’re on the streets, you realise that so many of those you meet are ex-Services. And all for the same reason: they are single; they cannot afford a house; and they don’t know where to go for help. Part of this is down to pride. Soldiers learn to act a certain way; to be totally self-sufficient. There is no-one when you come out to point you in the right direction. In the Army, your life is run for you, but it’s not like that on Civvy Street, and that’s why veterans like me should never hold back in asking for help.”

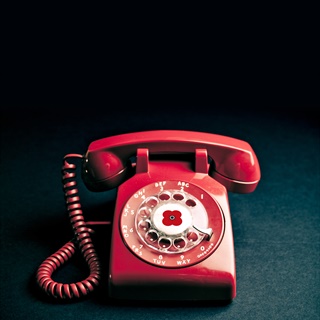

It was because Donald followed his own advice and sought help after being made medically redundant from SVR that his journey took him to Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory. He was referred to the factory management team by Combat Stress and they made the approach on his behalf. It is there, in Edinburgh, where a team of around 40 veterans produce four million poppies and 14,000 wreaths each year – by hand – for the Scottish Poppy Appeal.

Donald soon settled into his new role: “I started making poppies at first. I could manage 16,000 to 21,000 in a week. I then moved to wreath-making. After that and when the job became too much for the handyman, they asked me to take it over. That was perfect for me because, ever since I was a boy, I’ve always loved building things and taking things apart. I loved woodwork and art at school.”

One of Donald’s key roles is to design and build gardens of Remembrance that appear in the likes of Edinburgh and Inverness each year to park the period of Remembrance. It’s a project he relishes: “It’s like art to me. When all the people come to see it, it makes me feel really chuffed. It gives me a sense of pride.”

And it’s a sure sign that life for Donald has come so far since his dark days on the streets: “Life now is great. I do get lonely sometimes, but I love working at the Poppy Factory. I’ll retire when I die. As long as I am fit to work, I will.”

“I just want to get on with life, enjoy life and not to go back to the dark days. And I want to help anyone with advice or who is in the place I was all those years ago. I don’t think any ex-soldier should find themselves sleeping on the streets. In fact, no-one should in this day and age.”