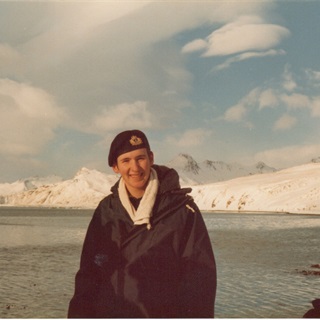

As an 18-year-old Able Seaman, James Garrett was sent to the Falklands with the Merchant Navy. He recalls keeping British forces supplied, while enduring regular air raids and assisting survivors in the aftermath of a bombing.

As a schoolboy in Stranraer, James Garrett remembers listening to his older sister’s boyfriend’s stories of life in the Merchant Navy. He said: “He would come home on leave and talk about all the different countries he’d visited. I thought it sounded exciting, and it became a dream of mine. I joined up after I left school, and I never regretted it.”

James quickly took to life on the sea, making friends from across the UK. In 1982, he was 18 years old and waiting for his next job when he took a phone call from the local office.

He said: “She told me the ship was in Southampton and was sailing ASAP. When I told my mum I’d just got offered a job in the Falklands she told me not to do it. But I was one of three boys, and my dad was in the Army. I think he was a little disappointed that none of us had joined up. So, at the back of my mind, I thought he’d be proud of me. I packed and left that night, and we sailed the next day. We had some scary times, but I’d do it all again.”

Sailing to the Falklands

James joined the MV Baltic Ferry as an Able Seaman, leaving Southampton in early May, shortly before the QE2. They sailed south to Ascension Island, carrying 5 Brigade, as well as supplies, 105mm field guns and ammunition.

He said: “It was very exciting. There were boys from Hull, Southampton, Glasgow – all over the country. When we sailed there were loads of wee yachts following us, and everyone was shouting ‘Good luck’ and ‘Godspeed’."

"One day, we were painting the forepart of the bridge, watching the Army personnel fire off a few rounds. They called us down and we all had a shot of firing a gun. We stopped at Ascension Island, and there was a flurry of activity with helicopters moving stuff to a couple of RFA ships that were anchored with us. It was really warm and generally happy and fun aboard. Some of the soldiers onboard were catching small sharks. As we were leaving, we saw the QE2 go past – she was really flying.”

Darkening ship

At first, James had only expected to travel as far as Ascension to carry supplies. But both the weather and atmosphere on board changing as they were told to go on south. He said: “The weather started getting a bit rougher and things started getting a bit more serious. We had to ‘darken ship’ and no lights were to be shown – we even painted the portholes black.

"Eventually we met up with a convoy and moved into San Carlos. As it became light that morning you could see all the little campfires in the hills around us. I felt in awe of the amount of Royal Navy ships around us and watched Ark Royal sending off planes. At breakfast time our Royal Navy Lieutenant Commander Webb made a speech on the ship’s tannoy welcoming us to ‘the hottest spot in the world’. At that time we were all a bit scared."

“We had our first air attack shortly after. We had air raids about two or three times a day, and you didn’t really have time to think about things. We’d get the anti-flash gear on and go to our emergency stations. There was lots of ammo there, and I just thought, if we get hit, we’ll be blown sky-high.”

MV Baltic Ferry carried a huge range of supplies for the “fire brigade” – everything from ammunition to “boxes and boxes of socks and camouflage gear”. Stationed with around six others in San Carlos, barges would come to the back to unload supplies.

The bombing of Sir Tristram and Sir Galahad

On June 8th, they got word that Sir Tristram and Sir Galahad had been hit by Argentinian Skyhawks at Fitzroy. Both ships suffered major damage, with Sir Galahad engulfed in smoke and flames. Fifty-six British servicemen lost their lives.

James said: “I was on the bridge when the radio just lit up. We offered assistance and we ended up taking on survivors. They brought about 40 Welsh guards to us on a big landing craft. We fed them and gave them beds. The cook was going mad in the galley making bacon sandwiches, hundreds of them. Being a ferry, we had lots of beer, so about 10 of them came into the bar with us. They seemed quite jolly, just having a craic and a drink with us. I remember sitting there wondering what these guys had seen. A lot of us were just boys, and it was a scary time for us all. Then we got up the next day and did it all again.

After the ceasefire

On June 14th, they received a telegram that there was a ceasefire, but were warned to stay on high alert. They sailed into Port Stanley alongside the Canberra, carrying extra ammunition and field guns in case they were needed. Finally, they were allowed to disembark and go on shore.

He said: “The first time we went ashore it was so strange. There was an Argentinian gun ship just lying abandoned on the beach. In Port Stanley, we saw money and stamps just thrown about the streets. A shell had gone through the Post Office roof. There were also guns and helmets just lying around.”

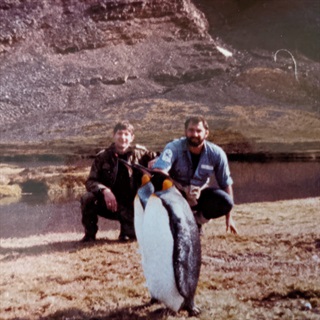

James took a ride in an Army helicopter to the island, meeting an old schoolfriend of his mother’s who had moved to the island. She was delighted to see a face from home and invited him in for tea.

In August, James travelled back as part of a convoy, to be reunited with his family who held a big party to celebrate.

A life at sea

James stayed in the Merchant Navy, fulfilling his boyhood dream to travel all over the world. Now aged 58, he lives in Kirkcolm, near Stranraer with his wife, and works with Stena Line Ferries. They have two grown-up daughters and two grandchildren.

Looking back, he said: “I don’t talk about the Falklands much, although I still stay in touch with some of the boys from Liverpool. I might dig out my medal this year. It’s hard to believe it was 40 years ago – some of my memories seem like it was just a week ago."

“A lot of people gave their lives, and I think it’s important to remember them.”