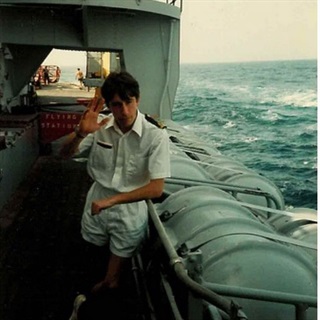

Graham Walker, a young Leading Seaman (Radar), was looking forward to deployment in the Far East and Australia when his ship was ordered to turn around and head for the South Atlantic instead.

Aboard the “Crazy Y”, Graham remembers freezing conditions and the constant threat of air attack, as well as “pummelling” Argentinian forces and going to the aid of ships in distress.

In early April 1982, Graham and his crewmates aboard HMS Yarmouth had just completed a Royal Navy training exercise in Gibralter. Like many others at the time, he knew little about the Falklands, but was “not very pleased” when their plans changed. “I didn’t know how far away they were. Reality only hit home when we started preparing and restoring the ship,” he said.

Graham had joined the Royal Navy six years earlier, as a 15-year-old school leaver from Beamish, County Durham. “I wanted to travel the world,” he said. “At first, I thought I’d join the Merchant Navy, but you had to pay to go to college and my family couldn’t afford it. So I joined the Royal Navy instead.”

Sailing south

HMS Yarmouth headed south her sister ship, HMS Plymouth, HMS Glamorgan, HMS Broadsword, and supply ships, stopping at Ascension Island on the way.

Arriving on April 30th, their first mission was to sail into San Salvador Creek, under cover of darkness, to pick up SAS members who had been dropped by helicopter on the island.

Graham said: “We were told to pick them up and then get the hell out. I remember that the kelp was so thick, we almost couldn’t go in at first because it was wrapped around the propeller. Everyone was walking on eggshells. We could see the Argentinians in the distance. We had everything switched off so they wouldn’t see us.”

The Ops room

Based in the Operation “Op” Room, Graham’s schedule would be six hours on watch and then six hours off for most of the next 156 days. At “actions stations” here was no down time and cold, sleep deprivation, and being constantly alert became features of everyday life.

He said: “We were heading into the Antarctic winter, and we didn’t feel prepared. We wore our work gear and overalls, then any civvy jumpers we had. Sometimes we folded newspapers between the layers just to keep warm. When we had a break from the action, some of us would lay down next to the radar displays as it was a warm area of the ship.

“We all tried to look out for each other. I think the older guys were quite worried but the younger crew members led the way with enthusiasm and courage which was infectious, and old and young worked together well as a team.”

He remembers hearing news that the Belgrano, the Argentinian cruiser, had been sunk by the Royal Navy submarine HMS Conqueror on May 2nd, 1982. He said: “No one clapped or cheered. We just looked at each other. That was when reality struck that approximately 360 fellow mariners had just died.”

Rescue missions

Two days later, HMS Sheffield was hit and badly damaged by Argentinian air forces, and HMS Yarmouth, along with HMS Arrow, went in to assist survivors. Graham said: “They were distraught. There were a lot of burn injuries - the fuel from the Exocet had exploded, killing about 20 crew members.”

They identified an Argentinian submarine lying in wait for other ships and attacked it with motor bombs, before towing the Sheffield to a safe area for salvage. Unfortunately, bad weather forced her to slip the tow, and the damaged ship slipped silently to the South Atlantic.

On May 20th, they sailed into San Carlos, tasked with escorting ships carrying the Army and Royal Marines into the bay. Nicknamed “Bomb Alley”, the area was under frequent attack from the Argentinian air force.

Graham said: “It was frightening when the Argentinians started advancing. We had small arms in the Ops room, and then machine guns all around the upper deck. The planes came in waves, and they were so close you could see the pilots. As they went overhead, we basically put a sheet of lead up in the sky for them to run into. We hit a few jets, and they exploded into bits.

“HMS Ardent got hit, and we went in to rescue the guys. Her stern was on fire, so we reversed in to take off the crew as their Captain ordered abandon ship. At that point, another air raid came in. As Yarmouth broke away, Ardent’s anchor cable had entangled Yarmouth’s propeller. Our Captain ordered full astern and broke free – if not, we would’ve been bombed.

“We got the survivors off and got them back for tea and biscuits. Not a medical cure for trauma but in the initial onset it helps!”

Daily routine

At times supplies would run low on board, and there was little time for niceties such as washing or sitting down for meals.

Graham said: “No one had a wash or a shower for weeks. You just basically stayed in your clothes. We just ate what we could – lots of tinned sausages, and you’d be armed with a fork in case someone tried to steal your sausage.

Letters from home arrived sporadically and were usually weeks out of date. Graham’s fiancée, a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, knew more than most civilians what was going on, and anxiously followed the news at home.

The final battle

As the British troops advanced on Port Stanley, HMS Yarmouth provided naval gun fire support.

Graham said: “We were on the gun line for five days. hammering shells in to Mount Tumbledown. Then you had to race like hell to get out of the Exocet range. We could hear their shells hitting the water and bursting, then the tinkle of the shrapnel hitting our ship. There was no time to be scared – the training kicked in and you just had to get on with the job.

“Each day we fired approximately 250 shells, then left the gun line to re-ammunition and refuel outside the range of Argentinian fighter jets. However, the Argentinians had mounted an Exocet missile system on the back of a lorry, and one of the missiles hit HMS Glamorgan. We heard all the alarms go off – 13 were killed in that attack.

Two days later, the Argentinians surrendered. Graham said: “When we heard, we were just ecstatic that it was over.”

After the ceasefire

The crew’s final mission was to sail down to Thule, one of the southernmost of the inhospitable Sandwich Islands, to re-take it. After a volley of 4.5 shells, the Argentinians surrendered, and the crew took the prisoners of war back to Port Stanley. Then in early July, they set sail for home.

Graham said: “We’d sit on the deck and have a barbecue and a few beers. It was just relief really, not a celebration. We were told to ‘splice the mainbrace’ (have a celebratory drink) and the tots went round. We just felt grateful to be alive.

“But then it hit us when we were on our way home. You’d find lots of guys just sitting in the corners of the ship quietly, on their own. We’d had 156 days with very little sleep, running out of food at times.

“It was strange being home, like another world in which you had to adjust. We had a party in my village at the local working men’s club. There was a lot of drinking in that time, and I remember looking at people and thinking they had no idea what war is and what impact it can have on people.”

Return to the Falklands

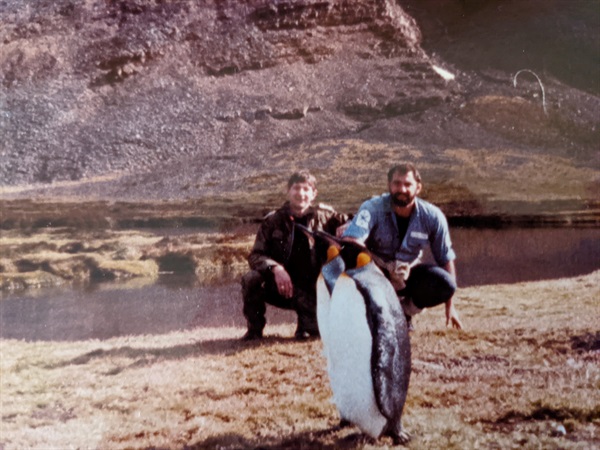

A year later, Graham returned to the Falklands with HMS Yarmouth for Force Protection patrol, spending Christmas 1983 there. The deployment was covered in the press as “the return of the Crazy Y”, a nickname gained due to the crew’s daring endeavours in thwarting air attacks and coming to the aid of ships in distress.

“It was totally different that time. We got to go ashore and meet lots of the islanders, who were in high praise of Yarmouth and very grateful for what we’d done.”

Civilian life

Graham stayed in the Navy for another 18 years, serving in the first Gulf War and Yugoslavia. He was promoted to Chief Petty Officer and spent his last few years teaching Maritime Warfare & Digital Picture Operations at RAF Boulmer Fighter Control School near Alnwick, Northumberland.

On leading in 2000, he decided to put these skills to use, gaining a teaching degree and Master’s in business. He went on to become a lecturer at Carnegie College (now Fife College).

However, civilian life wasn’t always easy. Shortly after attending a 25th anniversary event for the Falklands War in London, Graham’s memories came flooding back. With support, he managed to get through this difficult period, and encourages other veterans to seek help when needed.

He said: “Service life really puts a strain on families and relationships. Once you’re on the ship you transfer to another zone, and your family are so far away. It’s not much fun for them either.”

Graham met his second wife Marion at Carnegie College. The couple are now retired and live on a smallholding in Burntisland, Fife. Graham has a grown-up son and daughter and two stepdaughters.,