As a teenage drummer from Glasgow, Graham Hopewell was inspired to join the Scots Guards after seeing their band play for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. Aged 19, he didn’t expect to find himself sent to a war zone 8000 miles away in the South Atlantic.

The son of a Second World War RAF veteran, music was Graham’s passion growing up. He played the drums with the Boys’ Brigade and remembers seeing the Scots Guards Pipes and Drums band play in Glasgow in 1977.

“I thought that’s a better band than I’m in,” he said. He joined up the following year after leaving school at the age of 16. It was hard at first, but the band was brilliant,” he said.

After training at Guards Depot in Pirbright, Surrey, Graham took part in an exercise in Kenya then public duties at Chelsea Barracks. He was on leave in 1982 when they were told to return and prepare to go to the Falklands.

“It was a surprise for everybody,” he said. “I always thought the Falklands were near Falkirk, but I was wrong. We were sent on a training course in air defence in Wales, learning to use machine guns and shooting down drones out of the sky. Then we set off on the QE2, stopping at Ascension Island on the way.”

In the thick of it

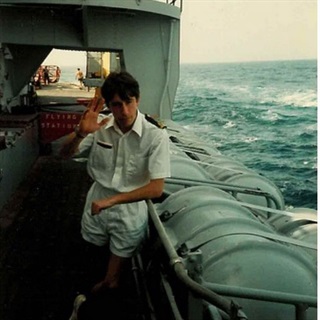

As part of 5 Infantry Brigade, the Scots Guards’ initial role was to provide back-up for the troops who had already arrived. After several weeks at sea, they transferred to HMS Canberra, and then landing crafts to arrive at San Carlos Bay. Here they “dug in” but were soon ordered to return to a ship to be transferred to Bluff Cove early on the morning of June 8th.

Graham said: “As we came into Bluff Cove on the landing crafts, we were being shot at by Argentinian ground troops. It turned out we were the lucky ones, as we landed in the dark. About five hours later the Welsh Guards were hit (on the Sir Tristan and Sir Galahad). By this time it was daylight, so it was easier for the Argentinian aircraft to see them. We couldn’t see it, but we heard this massive explosion.

“When the planes came over the top, we were shooting at them. At the time, you don’t really think about it. The adrenaline was just going. Later on, when we heard the ships had been hit, we realised it was real. I knew some of the Welsh Guards well. One of them, Eirwyn Phillips, had joined up with me and he was killed in the attack. That was a huge shock. I think this made us even more determined to go in and get it sorted out, so they hadn’t lost their lives for nothing.”

More than 50 crew members and soldiers died in the explosions and subsequent fire, with more than 150 wounded. It was the greatest loss of British forces in a single incident since the Second World War.

Daily routine

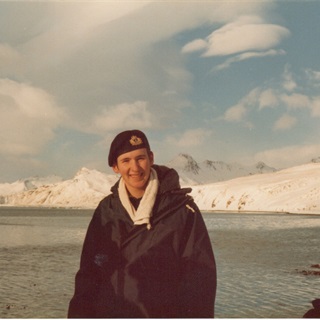

Graham remembers daily life in the Falklands as bitterly cold as the Antarctic winter approached, with supplies of food, kit and ammunition running low at times. They slept packed into sheds when not out in the open.

Soldiers on the ground received little information about what was going on elsewhere.

“It was very cold, very wet,” he said. “It looked a bit like the Highlands – very barren and bare. We felt that we were very far away and didn’t really know what was going on. We weren’t told anything – the passing on of information wasn’t very good.”

The Battle of Mount Tumbledown

After Bluff Cove, Graham was assigned to protecting the commanding officers. As part of the escort party, they were dropped off by helicopter close to Mount Tumbledown.

“The companies had gone in to attack,” he said. “Then we came in to make sure the area was clear. It was scary. We were right up the front during the fighting, and I knew I was in the thick of it. We could hear the machine gun fire and saw lots of red dots from the tracers. The fighting went on through the night.

“At that time, your friends help you get through it. You’re all there as a team and you need to keep everyone together and help each other survive. On June 14th, we were pinned down for most of the day, and still receiving sniper fire from above. We didn’t find out about the ceasefire until mid afternoon.

“When we heard, it was a feeling of relief. But we also lost some good guys, so that was really hard.”

After the ceasefire

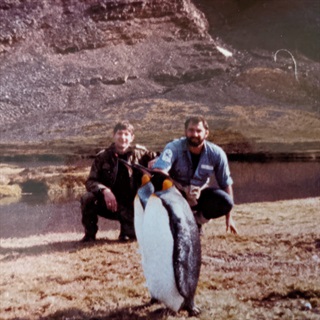

After that, Graham and his battalion stayed on for a few weeks, cleaning up the island and playing small concerts with the band. Around 200 of them slept in a former meat packing plant, that had recently been used to house Argentinian prisoners of war.

Although conditions were still very basic, the atmosphere was more relaxed – although they did come across an unexploded bomb during a game of football. Graham said: “It wasn’t until afterwards that we really found out why we were there. We played for the installation of the Governor at Port Stanley, and we had the chance to meet some of the islanders. We realised they were British through and through, and they were really grateful for what we’d done. If we hadn’t gone, then the Falklands would have been taken off us.

The voyage back to Ascension Island felt long and tedious, but they were then taken by plane to Brize Norton, where he was greeted by his family and a welcome party. They were given six weeks leave but getting back to normal life would take much longer.

“I think giving us so much time off was a big mistake,” Graham said. “That was soul-destroying for a lot of people. We had no one to talk to about it, and I found it hard getting my head round it all. I was only 19, and it wasn’t something I expected to be doing in my life. I think everyone was affected by it in some way. For many of them, it took years before they were diagnosed with PTSD.”

Later life

Graham stayed in the Scots Guards for nearly 24 years, moving to the Transport Platoon, and being promoted to a Corporal. On leaving, he settled in Ayrshire with his wife, and they have two grown-up children.

Now aged 59, he works as an undertaker and feels that his experience gives him a special empathy in supporting bereaved families. He said: “I love my job. Every day is different, and you are doing a service for people at one of the most difficult times of their lives.”

Graham will be playing in Edinburgh this year as part of the 40th anniversary commemorations and plans to lay wreaths on the graves of fallen comrades.

The Falklands has always stayed with me. I still stay in touch with many friends, and I think it’s important that we remember those who gave their lives.

Graham Hopewell