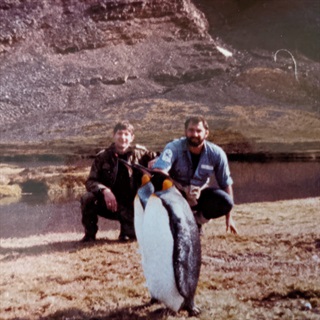

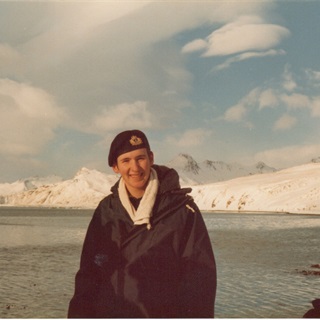

As part of the Royal Navy task force, Stewart Cooper, a young naval officer from Aberdeenshire, helped crew the first helicopter on a South Georgian glacier at the beginning of the Falklands conflict.

He went on to fly countless missions over the coming weeks, while his diary became a form of therapy.

On April 2nd 1982, following a training exercise near the Canary Islands, Stewart Cooper scribbled in his diary: Woke up this morning to find that we were on our way to the Falkland Isles to fight(?) the Argentinian Navy.

On board HMS Antrim, the crew had received little news from home. The day before, he and other sailors had become convinced that “something was afoot”, but their Captain had reassured them they would return to Portsmouth the following week. Now, at 4:30am, they were being told to change course for the South Atlantic.

Shortly afterwards, millions of people across the UK would be hearing the news that Argentina had invaded the British territory, with TV pictures showing their flag flying above the capital, Port Stanley.

The British task force was hastily being assembled – and Stewart’s ship, HMS Antrim, would be one of the first to arrive there. Over the next 10 weeks, his diary would record countless helicopter missions, the sinking of a submarine, and the sheer terror – as well as frequent boredom – of the conflict.

Working his way up

Sailing for the Falklands

Landing on a glacier

Sinking the Santa Fe

Daily routine

Air attacks