Daily life

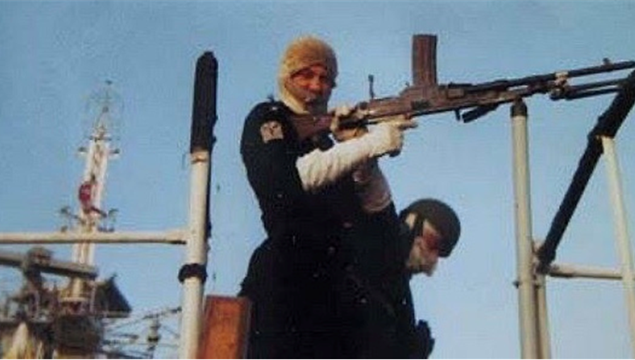

Life on board could be exhausting, with crew members snatching a few hours sleep or a bite to eat when they could. Some days, they would be at “action stations” or on watch for 18 or 19 hours at a stretch.

Graham said: “We used to sleep fully clothed, in our overalls in a bunk with a gas mask next to you.

“We had better food that the lads on shore. It was a case of grabbing something when you could, but we never went hungry. We ate a lot of sandwiches and ‘action snacks’ while we were at action stations.

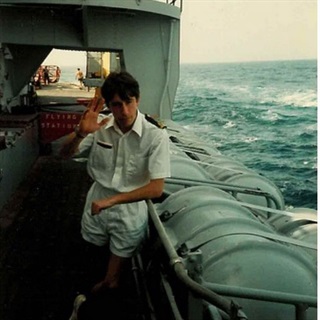

“We would write Blueys (airmail letters) to family at home. My mum got together with some other local mums to send Red Cross parcels out to us. They’d send sweets, music cassettes, newspapers (very out-of-date of course!) – anything to keep morale up. Afterwards, they got a nice letter from Prince Charles thanking them for their efforts.

“I was only 20 years old at the time, and at that age you think you’re invincible. You never think it’s going to happen to you. But I do remember thinking: ‘If my time’s up, I hope it’s going to be quick. I don’t want to suffer.’”

The end of the conflict

As British troops advanced towards Mount Tumbledown, HMS Yarmouth provided naval gunfire support, shelling Argentinian positions on shore. Then finally, the crew received the news of the ceasefire on June 14th.

Graham said: “I felt relief and elation, mainly because my parents wouldn’t be worrying anymore. But there was also sadness, because so many had died. A few weeks later, I felt even more sadness when I found out that a lad I went to Sea Cadets with, a Royal Marine, had been killed.”

After that, her final task was to sail south to Southern Thule, re-taking the Sandwich Islands. Then finally, the Crazy Y was one of the last ships of the initial task force to be sent home.