Drum Major Willie Urban joined the Scots Guards when he left school as he “didn’t want to go in the pits”. A few years later, he found himself in the Falklands, shooting at Argentinian planes and finding a bomb during a football match.

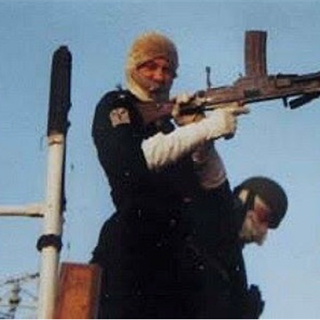

Sitting on his desk at Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory is a photo of Willie Urban, in Army fatigues, standing on a hillside with a machine gun. Behind him a fellow Scots Guard scours the bleak, exposed landscape of the Falklands with binoculars.

The picture was taken in Bluff Cove in June 1982, shortly after a devastating Argentinian air attack had claimed the lives of dozens of Welsh Guards in the nearby harbour. As the planes roared overhead, there was no time to think first.

“I’d never fired that gun before,” Willie said. “There’s nothing in training that can prepare you for that. At that point the adrenaline just takes over. When I got back to the base afterwards my hands were still shaking.”

Joining up

Willie, now 65, was a 25-year-old Drum Major when he was posted to the Falklands with the 2nd Battalion, the Scots Guards.

He joined up after leaving school at 15 in November 1971, despite some concerns from his family. Apart from an uncle in the RAF, he didn’t have any family members in the military.

“I didn’t want to go in the pits like my father,” he said. “It was pretty scary at first, but I soon got into the swing of things.”

He was sent to Pirbright, Surrey to do his training for two years before his first posting to Germany. While home on leave, he met his wife on a night out at a working men’s club, and they married in 1975. Three days after their son was born, he was posted to Belfast on the first of four tours of Northern Ireland.

Willie had played the drums a little before joining the Army, and soon took the opportunity to train as a drummer. One of his favourite memories was having the chance to tour North America with the battalion’s band, spending three weeks playing concerts from New England to the West Coast. He also played in front of crowds at the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace.

A change of plan

In Spring 1982 Willie was stationed at Chelsea Barracks in London and had been charged with running a pop-up stall selling souvenirs on Horse Guards Parade for the day. Wearing the iconic Scots Guard uniform of a red tunic and bearskin hat, he expected a day spent chatting to tourists and posing for photos.

“The Falklands were just brewing,” he said. “I knew the Americans were having meetings with Margaret Thatcher, but no one expected this. Then suddenly we were called into the gymnasium by the Commanding Officer and told to bin the red coat and furry hats and get on the green kit. We were sent to Wales to do training.

“I didn’t join up to go to war, but this was what we’d trained for. I knew nothing about the Falklands, I didn’t even know where it was.

“My wife accepted it was my job. She had enough on her plate as our youngest child was just five months old.”

Sailing on the QE2

Willie and the rest of his battalion trained in the Welsh hills to prepare for the inhospitable terrain of the Falklands. They set sail on the QE2 on May 12th, stopping at Freetown on Ascension Island for supplies during the three-week voyage. With the Welsh Guards and Gurkhas, they were part of 5 Brigade, and thought they would be acting as back-up to the troops who were already there.

Willie remembers: “When we first got on the QE2 it was lovely. We were getting great service, but that soon changed when the Army chefs took over!

“We could write ‘Blueys’ (airmail letters) home. When I got letters from my wife, I had to destroy them afterwards.

“We had to practice live fire and target practice on the bridge and were running round the decks or doing weapons training. We were kept fit on the ship, and had lectures about this and that, and looked at maps.

“Reality started hitting home when they started blacking out the portholes and doing night guards on the bridge.”

Digging in

They landed at South Georgia and transferred to SS Canberra before landing at San Carlos. As a drummer, Willie’s platoon initially had a defensive role as part of Battle Group Headquarters.

He remembers when they were first sent ashore: “It was wild, rough terrain. It was cold, and the ground was boggy. They gave us galoshes to wear over our boots, but some wouldn’t wear them. They got trench foot, like back in the First World War.

“It was a case of get in, build up shelters and get settled in. We just had to get on with life as best we could. We had to prepare ourselves for the unknown.

“One day we were all sitting in the trenches, and we heard a boom. We were all taking cover. An artillery officer said: ‘That’s not for you guys.’

“They were bombarding the mountain. The Navy and RAF were coming in. It was like fireworks in the night. We could see the attack going on. It was like it was in slow motion. The machine guns have a tracer that lights up. They blew the top of the mountain off.”

Bluff Cove

The platoon was transferred by ship to Bluff Cove in early June during a night he describes as “one of the scariest ever” as they battled high waves in the South Atlantic.

On June 8th, the Argentinian air force bombed ships anchored close by in Port Pleasant in one of the most devastating attacks of the conflict. Two ships, Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram were hit by five Argentine Skyhawks.

Sir Galahad burst into flames instantly, with survivors jumping into the water to escape. Around 48 members of the Welsh Guards lost their lives.

Willie and his platoon were stationed on the other side of the hill as the air attacks took place.

He said: “The Argentinians came through the valley, and the first wave hit the ships really badly. The next time they came through we were ready for them, firing from the hip.

“They were so close you could almost see the pilots. We thought they were dropping more bombs on us, but it was only the fuel tanks to get more height and get away.

“We saw the smoke coming from the bay. It was only later that we learned what happened. The ships were in flames, and there were guys diving into the water trying to get away from the burning ships.

“It was horrendous - the biggest loss from one regiment. I had many friends in the Welsh Guards who lost their lives.”

The Battle of Mount Tumbledown

A few days later they were ordered to move forward to Goat Ridge, just outside Port Stanley, within “touching distance” of Mount Tumbledown. On the night of June 13th, they were part of the defence platoon, prepared to go in to replace casualties if required.

They could see the battle taking place in the early hours of the morning, with casualties brought back to them on stretchers. Eight Scots Guards were killed that night, as well as a Royal Engineer who was attached to the battalion.

“After the ceasefire we moved on to Mount Tumbledown,” he said. “Everybody was walking about in a daze, but still switched on. In a way they were shellshocked.

“I think if the battle had gone on for another couple of hours, then we would’ve lost. We were running out of ammunition.”

After that, they were sent back to the ship for a bit of “R&R” (rest and recuperation).

“We were trying to calm down, but there were people walking about like cripples because of trench foot,” he said. “Then we got hurled off the boat so they could take the prisoners back to Montevideo.

“After that, we had to stay until August to clear up. We had to go round the island and dismantle trenches and take away barbed wire.

“We were more relaxed, but you still had to be alert. One day we were playing five-a-side football, and we found an unexploded bomb at the back of our accommodation. They managed to get rid of it.”

Home at last

Willie finally returned home to be reunited with his wife and young family. He continued his Army career, including serving as a drum instructor at Guards Depot, before he was discharged in 1996 after 22 years.

“Oh God, I miss it,” he said “If I could do it again, I would. When I was 15, I was going into the unknown. I’d never left home, never been out of Scotland. I got on that train to Kings Cross and never looked back.

“It had its ups and downs, but I stuck at it, and made friends for life.”

Willie took a variety of jobs, including as a security officer and bus driver. He learned about Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory through a friend who was the foreman and has now been working there for four years.

He lives in Newtongrange, Midlothian, with his wife. They were proud when their son followed in his footsteps to join the Royal Artillery, going on to serve in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Each year, Willie travels to Blackpool with fellow members of the Tumbledown Veterans and Families Association, reuniting with old friends and comrades and remembering the fallen. Last year, they laid a memorial plaque on the seafront in memory of the Scots Guards who were killed in the battle.

“We’ll never forget them,” he said. “It’s a big milestone this year, and I’m looking forward to it. I’m still very close to all my friends from the Scots Guards. None of us are getting any younger now, and it’s important to remember what happened.”